There’s an old expression that gets a lot of use in engineering and research circles; I’m sure you’ve heard it:

When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

If you’ve spent your career studying control theory, everything looks like a dynamical system. If you’re an ardent TDD pracitioner, every bug looks like a failure of testing. If you’re a machine learning engineer\(\dots\) you get the idea.

There’s a lot of value in using tools you know well to solve problems quickly. It gives you a framing that you can use to get traction fast. If you ask 5 people with different hammers about the same problem, you’ll get 5 different diagnoses and 5 different solutions. Some will be better than others. Considered together, you’ll get 5 perspectives on the same problem, and some ability to evaluate which fits best.

Sometimes, when you’re deep in a problem, you can’t collect 5 people with different hammers to quiz. Maybe the problem would take too long to explain, maybe all your friends have the same hammer you do.

You start by hitting the problem with your hammer. If you’re lucky, you’ll have two or three hammers you can try out. The problem with hammers is that you can keep swinging them all day long. Nothing will ever stop you. Usually they’ll even keep working, a bit. That makes it hard to realize that you need a new hammer.

For some problems, the gains you get from using a hammer that you’re extremely skilled with are outweighed by the inefficiencies of using the wrong tool for the job. If you hammer on a screw long enough, you’ll eventually sink it (don’t ask me how I know). But it will take a lot of effort, and it won’t hold very well.

Recognizing those situations isn’t easy. You can’t know from the beginning. But once you start swinging that hammer, how do you know when to stop and look for a better tool?

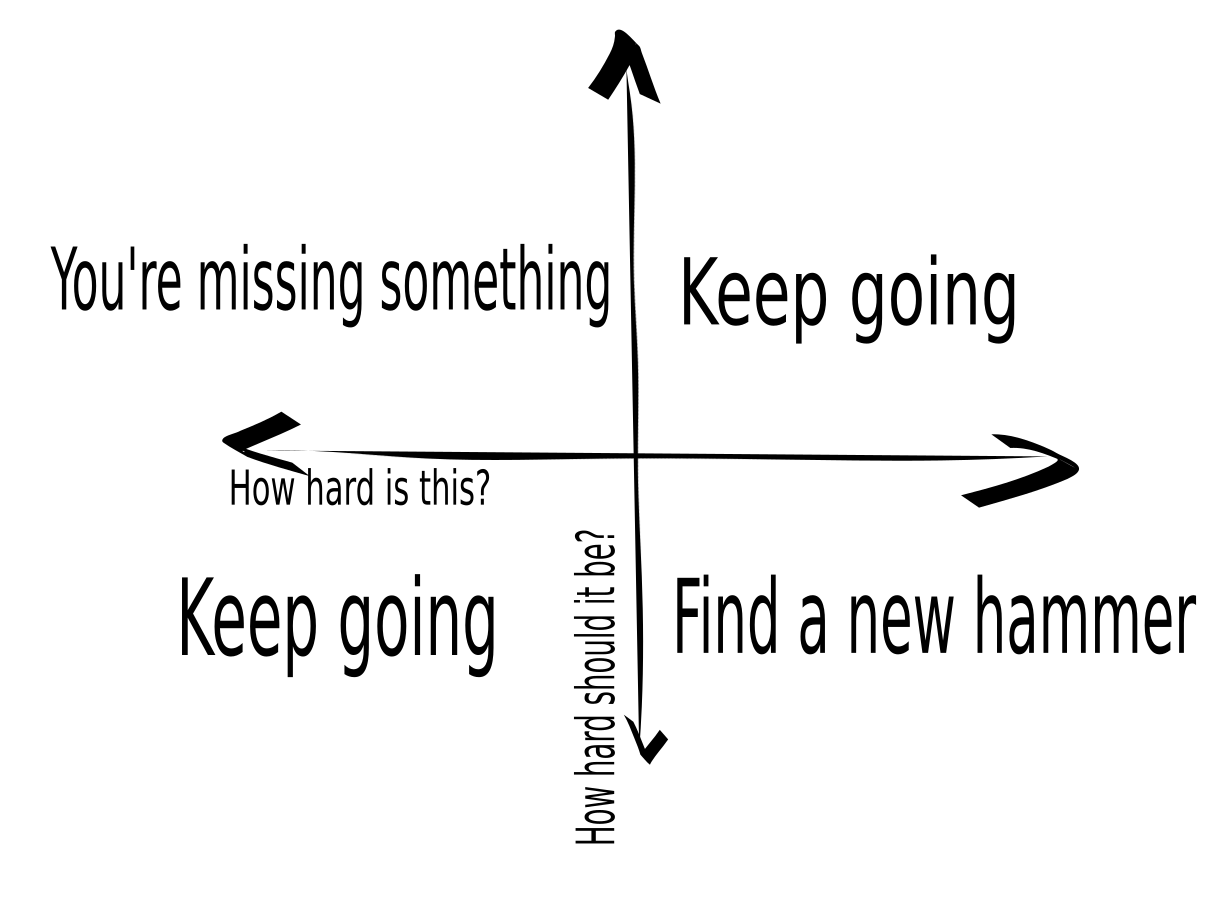

I like to visualize a space with “How hard is this” along one axis, and “How hard do I think this should be” along the other axis. It’s helpful to know where you are in this space at all times.

If it’s easy and it should be easy, you’re fine. If it’s hard and should be hard, you’re fine. If it’s easier than it should be, then you’ve either misunderstood the problem or your solution doesn’t work the way you think it does. If it’s harder than you should be, you’re not using the right tool for the job. You need a new hammer.

When you start, you don’t know how hard the problem is. With experience, it becomes easier to make good guesses about how hard something should be ahead of time, and how hard your solution will be ahead of time. But you never really know.

As you work, you get a better sense for where you are along both axes. The problem is that you can easily slip into that bottom right quadrant without ever noticing. It’s a good idea to develop the practice of checking in with yourself about how you understand the problem, and how you understand the solution.

Once you realize you need a new hammer, there’s a whole host of other questions to face. Which hammer? How do you find out? If you find one, how do you figure out if it will work? Questions for another time.